Carbon Accounting Management Platform Benchmark…

2020 marked a year of great change in China's approach to data protection and privacy – how will these changes impact companies seeking to enter China's vast digital economy.

An overview of the existing regime

With the world's largest digital economy, made up of over 900 million internet users, data protection and privacy policy have gained growing attention in China over the past 5 years. Currently, China has no single comprehensive legal regime for data and privacy law (i.e., no equivalent to the GDPR). Instead, the current regime is set out across several national laws, some imposing direct obligations onto operators, while others authorise the State Council and its ministries to enact regulations. The result is a fragmented system, one in which it is very difficult to point to a single set of obligations that companies should follow in order to comply.

The most important law currently in effect is the Cyber Security Law (CSL), which was enacted in 2017. The CSL is a broadly worded law that provides a general framework for China's data policy, leaving most of the specific obligations to be provided for by the various authorities through regulations. The most important of these is the Personal Data Security Specification ("the Specification"), which was updated in 2020. The Specification provides a much more comprehensive policy for the protection of personal information, many of which are very similar to the approach taken in the EU's GDPR. However, the specification is non-binding and acts as a set of best practice recommendations.

The central principle for the protection of personal information under the CSL is that operators must "abide by the principles of legality, propriety, and necessity". These principles are foundational to the approach of the Chinese system and generally recur throughout the various regulations. They can be described as:

In addition to the CSL, other important laws include the Civil Code, which protects individual's rights to privacy, the Criminal Law, which establishes offences for data abuse, and the Advertising Law, which sets standards for targeting ads.

A big shift in China's Privacy Law

In 2020, the Chinese government published a wave of new laws aimed at strengthening their approach to the national privacy policy, including publishing drafts of two major data protection and privacy laws. The first of the two, the draft Data Security Law (DSL) was released on July 3, 2020; while the second, the Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL), was released on October 20, 2020. These laws are expected to be enacted in 2021 and take effect by 2022[1]. These new laws represent an impressive improvement in the Chinese approach to privacy, and although the law remains seen to be scattered, these laws mostly codify and condense the current fragmented position into two single documents.

Although the drafts do not expressly repeal the CSL, they have the effect of replacing it and splitting the policy into two core components; cybersecurity and individual data protection. The draft PIPL is particularly impressive, as it codifies many of the principles set out in the 2020 Specification into law, whilst also adding a few new obligations, particularly in regard to cross-border transfers and data security. The draft PIPL is notable for its clear influence from the EU's GDPR, meaning organizations may be able to leverage their GDPR compliance efforts to prepare for compliance with the PIPL.

[1] Herbert Smith Freehills, China cybersecurity and data protection: Review of 2020 and outlook for 2021

While China's data law is often described as fragmented and disjointed, there are several key obligations that are consistent across the various laws and regulations, including the two draft laws. Three key obligations under China's data protection regime are:

Control – a more recent addition to China's approach to data protection has been the expansion of individual rights to allow for access and control of their own data. Operators must create mechanisms for users to access their data, request rectifications and raise complaints. Currently, companies are not obliged to delete data at the request of the user unless they have violated the laws. Under the Draft PIPL operators must cease using and delete the data of users if they rescind their consent.

While the two draft laws mark a clear focus by the Chinese government to strengthen the enforcement of data protection, they both focus on public enforcement. China's privacy law has also seen substantial development in private rights and private enforcement. The emergence of private enforcement is likely to accelerate after the enactment of the Civil Code in 2020, which for the first time provided an express right to privacy for Chinese citizens. The law establishes that where the right is harmed or infringed, the individual has the right to seek civil liabilities including requesting the infringer to "stop the infringement" or "rehabilitate his reputation"[2].

[2] The Civil Code (2020), Art. 995

Private enforcement has become particularly important in handling issues involving emerging technologies such as the implementation of facial ID across China. In 2019, a Chinese court heard the country's first-ever case regarding the use of facial recognition. The court found that a wildlife park's use of facial recognition "exceeded the legally necessary requirements, so it was not legitimate" and ordered them to delete the individual's data and pay them compensation[3]. As a result of the growing trend of private enforcement, many organisations have taken it upon themselves to develop data protection mechanisms to address the concerns of their customers. For example, an initiative backed by 27 major tech companies created the country's first industry standards for use of facial recognition. One of the companies, SenseTime, have said that the standards "will be guidance and foundation for the yardsticks of facial recognition in all fields"[4]. The introduction of these standards marks an important shift in the industry thinking towards data protection in China.

[3] Tracy Qu, ‘Chinese court orders wildlife park to delete facial recognition data as privacy concerns grow among Chinese citizens’, SCMP, 24 November 2020

[4] CSIS, ‘Coming into Focus: China’s Facial Recognition Regulations’, 4 May 2020

China has gradually increased the scope of their data protection laws to extend beyond its borders. The current position under the CSL is that organisations who send data outside of China must first obtain the consent of the individuals, informing them of who will handle the data and the purpose of its use. Beyond this, the CSL only restricts the transfer of data overseas for 'critical information infrastructure', which it defines by information, that if leaked "might seriously endanger national security, national welfare, the people's livelihood, or the public interest". The 2020 Specification provides a more detailed set of recommendations for handling international data usage - provides that operators handling data outside of China must conform to the requirements under national regulations and standards.

The incoming draft PIPL and the draft Cross-border Transfer of Personal Information, which was published for comment in 2019, provides more rigid and binding obligations. The draft PIPL only allows for the transfer of data if the operator either a) passes a security assessment with the State authorities; b) obtains a certification from an authorised body; or c) contracts with a domestic operator and agrees to follow local law.[5] The latter of these will likely be the most common method for operators to transfer overseas.

Operators should be careful when transferring data overseas. The vague language of the law makes it difficult to determine with who the responsibility lies. Overseas handlers should check whether the domestic operator has obtained the appropriate consent from individuals and have been authorised to transfer the data to a third party. Under this new regime, the Government would effectively have the power to ban overseas operators if they are found to be violating the privacy of individual citizens or pose as a threat to China's national security interests.

[5] Draft Personal Information Protection Law (2020), Art 38

As of March 2020, China's digital economy had grown to an unprecedented size, with over 900 million internet users, 4 million websites and 3 million mobile applications.[6] Additionally, Chinese consumers have quickly adopted new retail opportunities, with 639 million online shoppers and 633 million using online payment systems.[7] This massive growth in digital interactions has placed cybersecurity and data protection at the forefront of the Central Government's mind.

[6] Ashurst, ‘China unveils new draft data privacy law’, 9 November 2020.

[7] Bo Qu and Changxu Huo, 'Privacy, National Security, and Internet Economy: An Explanation of China's Personal Information Protection Legislation' (2020) 15 Frontiers L China 339, at 358

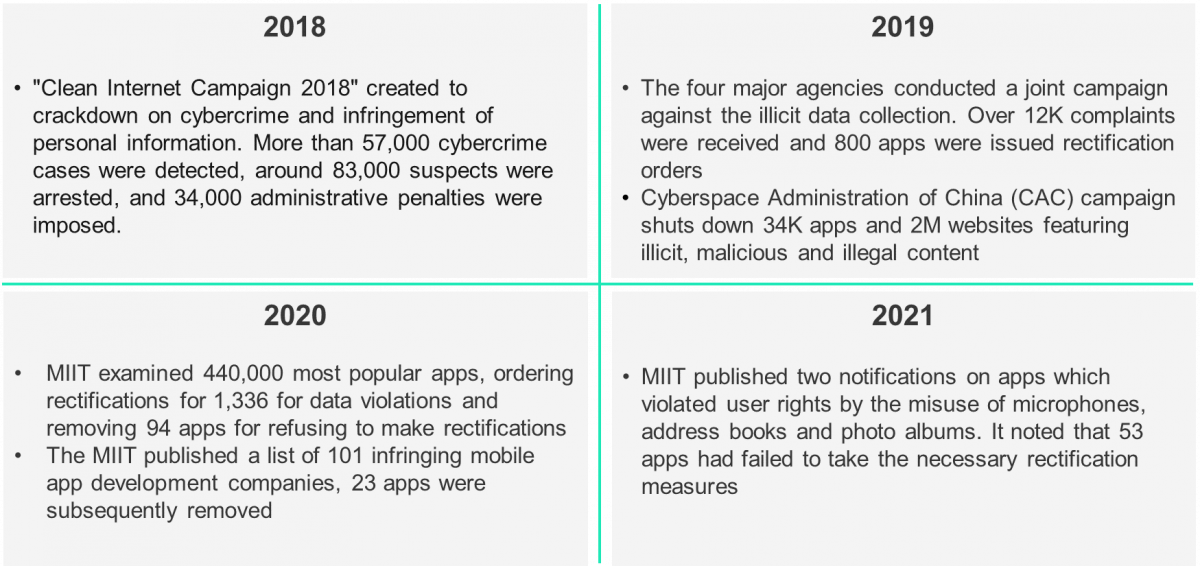

Companies interested in joining China's mobile app market must be particularly vigilant in following China's data and protection policies. The authorities have in recent years targeted app developers over data abuse and incidents of data leakages. In 2019, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) launched a campaign against apps infringing users' rights, targeting issues like the illicit collection and use of personal data, unreasonable requests for user authorization, and obstructing users from cancelling accounts. During the campaign, MIIT asked a third-party testing agency to inspect application stores and urged more than 100 companies with identified problems to rectify them.

To combat data abuses by app developers, the Authorities have issued several specific guidance notices and regulations that create new obligations for operators of mobile applications. These mainly focus on limiting app developers from collecting excessive amounts of data. In March 2021, the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) released a notice on the "Regulations on the Scope of Personal Information Required for Common Types of Mobile Internet Applications". In this notice, the CAC outlines the "necessary personal information" needed for the "normal operation of the basic function of the app" for 38 types of apps[8]. For example, apps providing a map navigation service should limit their data collection to "location information".

The Guide to the Self-Assessment of Illegal Collection and Use of Personal Information by Apps and the Methods for Identifying the Acts of Collecting and Using Personal Information in Violations of App Laws and Regulation are two guidance documents that provide detailed and specific requirements on the construction and demonstration of the privacy policy in Apps. They include the independence and readability of the privacy policy; the key elements included in the privacy policy; and the protection of users' rights to their personal information. For example, the guidance requires operators to make their privacy policy clearly accessible within 4 clicks after they open the home page of the App. Operators are also in violation if they set the users' consent as a default option, continue to ask for consent after the user has already refused to give it, or do not provide users with the option to withdraw the consent given. Finally, under the guidance, app operators should give users the option to receive pushed information that is not based on user profiling[9].

[8] Regulations on the Scope of Personal Information Required for Common Types of Mobile Internet Applications (2021), Art 3

[9] C’M’S, Activities that constitute illegal collection and use of personal data via Apps are clarified, 14 January 2020

Operators both domestically and overseas will need to prepare for further developments in China's data protection regime as the authorities continue to create new regulations to aid the implementation of the incoming privacy laws. As China's digital economy continues to grow and new technologies emerge, companies should not be afraid to maximise the growth opportunities that are present in China, but they must remain vigilant and compliant with the nations fast-developing data and privacy laws.

An innovative global consulting firm that is ahead of the curve, Sia Partners can assist your organization in anticipating imminent regulatory changes to strengthen your business and reduce risk. Our teams have built key experience and expertise in Data Privacy and Data Protection domains not only in Asia, but also in Europe and North America. In addition, we periodically publish regulatory updates on Data Privacy Laws in the APAC region (check the latest article).

This article was written in collaboration with Cameron Pollaers, law student at the University of Hong Kong.