Canadian Hydrogen Observatory: Insights to fuel…

Date of Analysis: 1st January 2021 until 30th September 2023

After the 2008 financial crisis, the European Central Bank (ECB) began reducing its key interest rates starting in October of that year. This trend continued into the early 2010s, especially with the emergence of the European debt crisis. In March 2016, ECB key interest rates reached their lowest point and remained stable until recently, with a minor adjustment in September 2019.

However, starting in late July 2022, rising inflationary pressures prompted the ECB to gradually increase its key interest rates to relatively high levels. Consequently, banks have been gradually adjusting the interest rates they offer to their customers. Customers have grown accustomed to low rates on various financial products over the past decade[1], they are now beginning to notice that savings accounts are providing significantly lower returns compared to other investment options like term accounts and bonds.

Given this situation, it is insightful to explore the strategies employed by banks in the Netherlands and Belgium to either retain or discourage the outflow of funds from savings accounts.

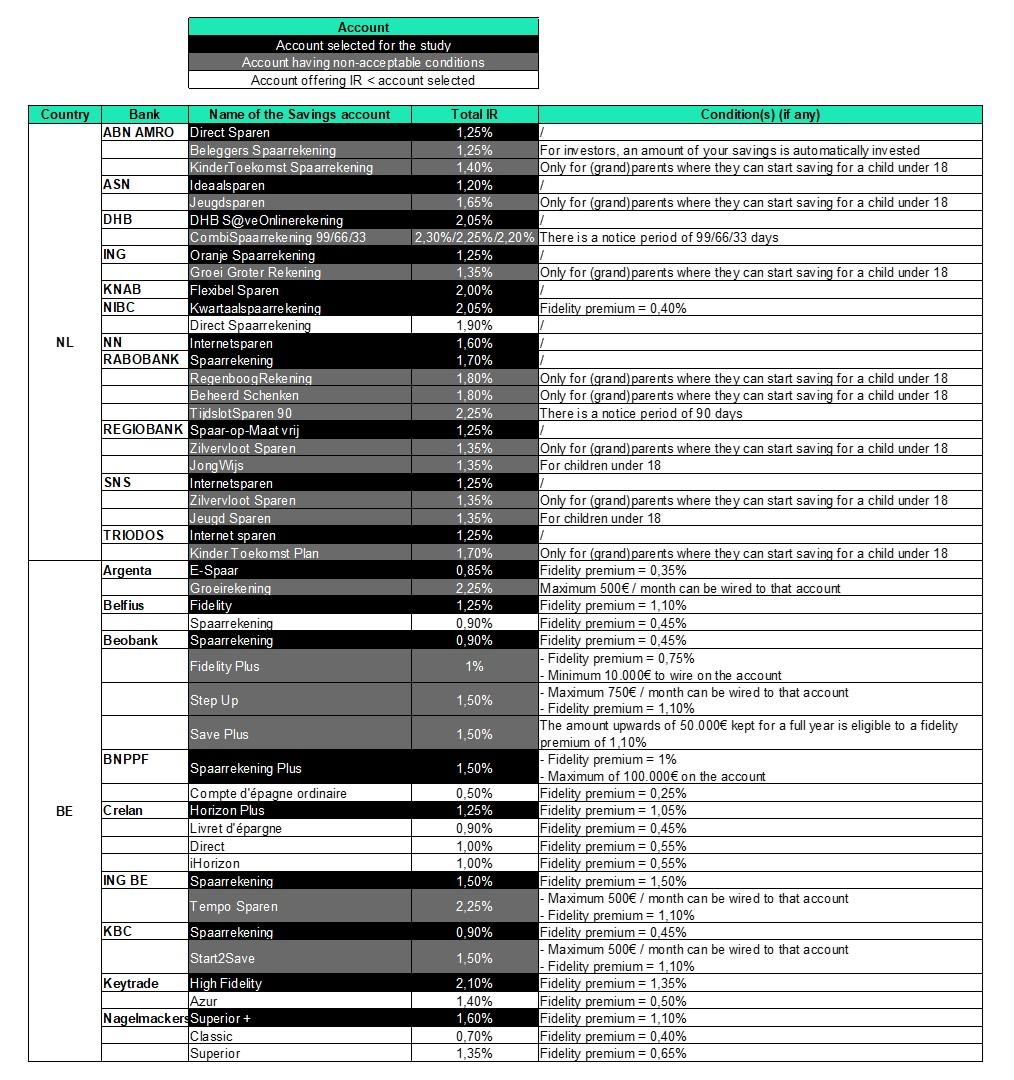

The top 10 banks in terms of market share in the Netherlands and Belgium were initially considered for this study. The banks for which pre-conditions are required to be a client were not included in the study. [2]

While the Dutch banks are limiting access to some savings accounts offered to a certain population ((grand)parent for their minor child), Belgian banks are offering higher diversity (more options for the general public). The main options proposed are:

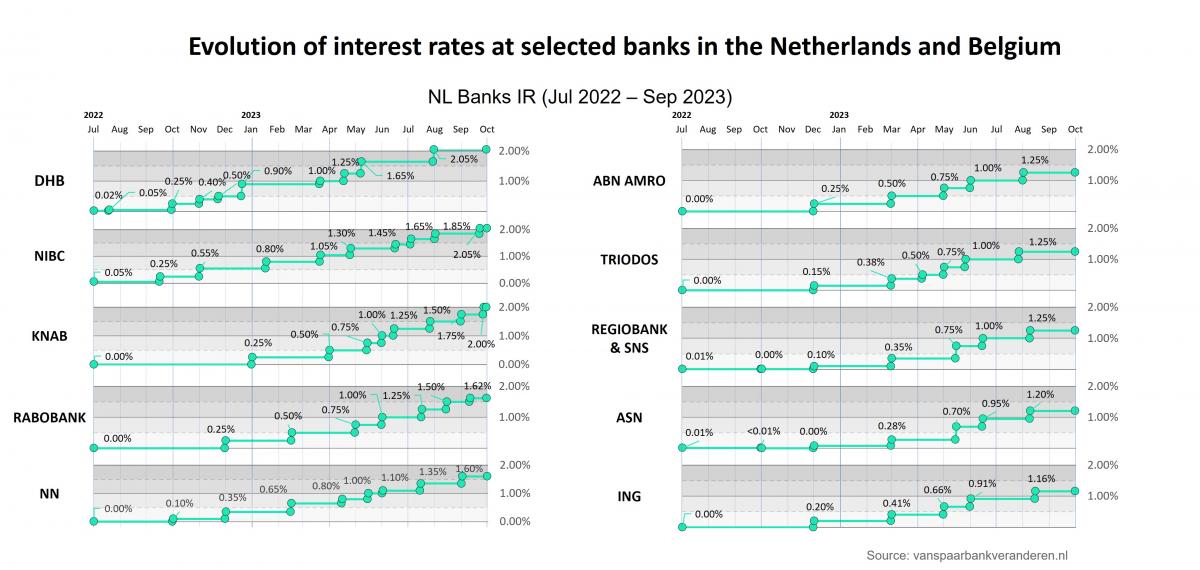

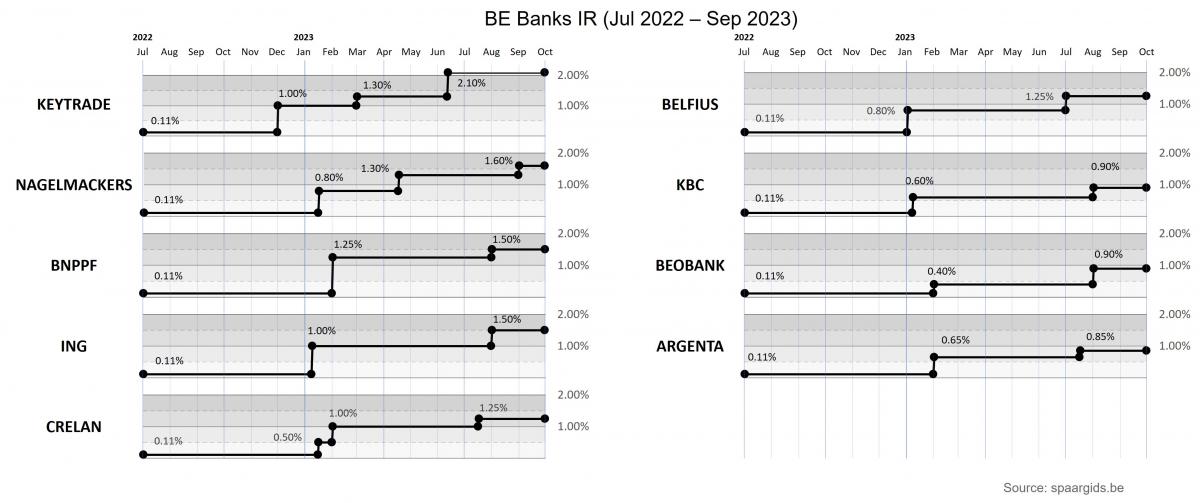

Interest rate data was collected from January 2021 to September 2023.

Since the interest rate received depends on certain conditions for some banks, and in order to propose a unique comparable figure, a synthetic average interest rate was computed with the following guidelines:

Let’s take the case of ASN savings account as an example:

Among our peer group representing the biggest banks in each country, the current average interest rate is slightly superior in the Netherlands (1,54%) than in Belgium (1,32%):

Regarding differences between the Netherlands and Belgium (especially regarding the timing at which banks raised their rate) it is interesting to note the following:

In summary, despite the banks gradually raising their interest rates, the speed of this increase remains notably sluggish.

Local governments are eager to express their concerns and take actions to promote change:

In the Netherlands, despite having a huge number of players, the market is particularly concentrated as the top 3 has a combined market share of 74%), the next 6 Dutch banks have a combined market share of almost 6%. The remaining 20% of the market share consists of a significantly high numbers of banks with a low market share each that are excluded from this study.

The Belgian market is more fragmented as the top 3 banks have a combined market share of 56% and only 3 out of the 10 banks in the sample size have a market share lower than 1%.

A negative but weak relationship between interest rate and market concentration is observed for both countries:

Smaller banks seem to often rely on the savings account interest rate as a prominent symbol of visibility to entice new customers.

Initially, Dutch banks had lower interest rates compared to Belgian banks:

When examining the time gap between the announcement and implementation of interest rate increases (referred to as delay), a slight distinction is observed between the Netherlands (20,5 days) and Belgium (19,8 days):

It is also interesting to note the interrelation between the moves of large banks in both countries:

The ECB has raised its key rates by over 4% since July 2022, but Dutch and Belgian banks have, on average, increased their savings account rates by less than 1.5%. In the Netherlands, smaller banks tend to react more swiftly to ECB interest rate changes, implementing rate adjustments more frequently and with less delay. Conversely, larger banks in the Netherlands respond more slowly, making smaller rate adjustments, and announcing changes well in advance. These differences likely stem from variations in their business models, with smaller banks often operating using alternative models, such as subscription-based approaches, enabling them to cover operating costs effectively and adopt a more aggressive strategy.

In Belgium, this division in responsiveness does not seem to exist, as all banks are slow to react and adjust rates less frequently in comparison with the Netherlands. This may partly be explained by the legal minimum interest rate in Belgium, which was (also) in place when the ECB had a negative interest rate and thus Belgian banks had to pay the ECB to hold reserves despite offering positive interest rates to clients.

With the ECB indicating on September 14th that its latest rate hike would likely be its last, economists generally believe that there is room for banks to increase savings deposit rates. It will be intriguing to observe how banks navigate this, taking into account potential shifts in customer behaviour and growing political pressure, especially from the Belgian government.

This study also highlights the diversity in savings account offerings, suggesting that many banks may consider offering higher interest rates on new accounts with stricter conditions to meet customer demands while maintaining profitability. Additionally, Dutch and Belgian banks must address options that allow customers to move their savings across multiple jurisdictions.

[1] NL: In 2018, 7% chance of switching savings account (partly influenced by interest rate) (DNB)

BE: Customers remain mostly loyal customers, there is barely a switch of savings account (VRT)

[2] The following banks were not considered:

[3] The following savings account offerings were not considered due to the stringent conditions linked to earning IR proposed: