Carbon Accounting Management Platform Benchmark…

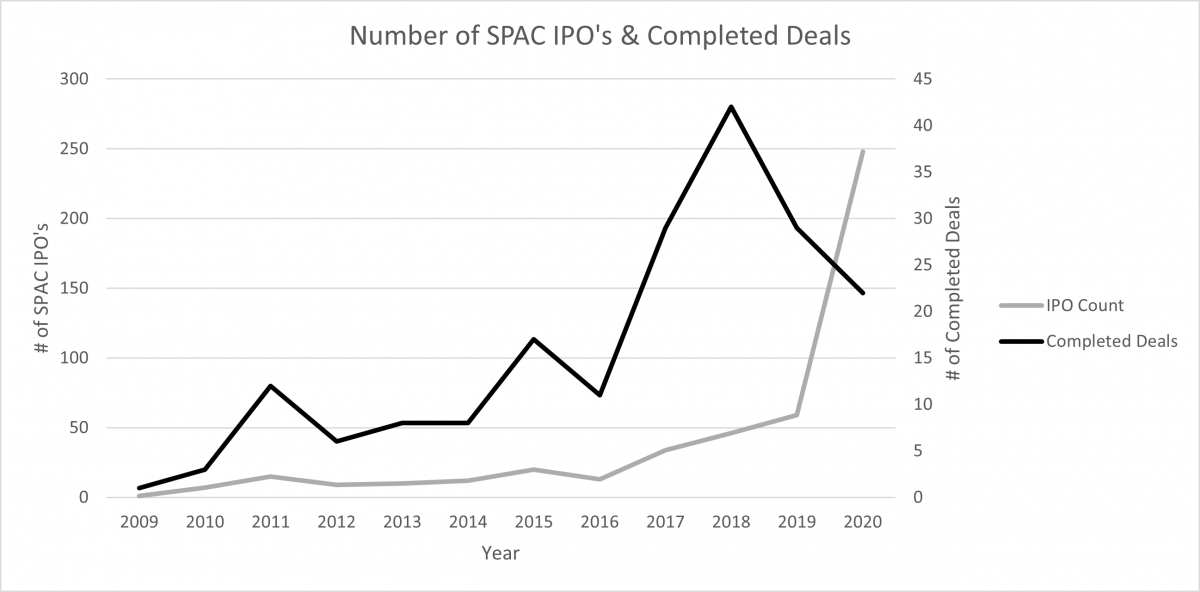

The SPAC boom recalls the reverse merger boom of 2010-2012, which did not end well.

What are the parallels, and what is different this time?

The media is flirting with the idea that SPACs may face a similar fate to reverse mergers in 2011.

Reverse mergers, also known as Reverse Takeovers (RTOs), allow private companies, including foreign investors, to gain access to the U.S. capital market [1]. In 2011 and 2012, abuse of RTOs eventually led the SEC to delist or suspend more than 100 U.S. listed Chinese companies and issue a warning to retail investors of the associated risks [2]. The SEC found substantial evidence of fraudulent accounting practices from overstated operations to the inability of newly public firms to report filings accurately and completely. RTO share prices fell by 45% and the volume of deals dropped substantially.

A Harvard Business Review article by Ivana Naumovska, in a lessons-learned approach, suggests that dynamics present during the reverse merger bust are re-emerging in SPACs: frenzied growth in a controversial financial instrument, and negative media and regulatory concern regarding the quality of the targets [3]. Additionally, as a “De-SPAC” transaction mechanically occurs through a reverse merger, it is hard not to link the two.

It's no secret that, like the RTO boom 10 years ago, there is a lot of “hype” and “froth” in the SPAC market, and plenty of resulting stock price volatility. And it is likely that some SPAC deals will fail to achieve mergers, and that post-merger, many SPAC deals will fail to achieve adequate returns on the money invested (note that this is also true of the traditional IPO market). That said, there are important differences versus the RTO saga, this time around.

A reverse merger is an alternative to the traditional IPO process to bring companies public. Rather than a private operating company raising capital in the public market, the private company may go public by acquiring a controlling stake in a dormant shell company, a thinly-traded company that no longer conducts business nor holds assets (or holds little assets). The operations, and typically the management, of the private company remain in the surviving public capital structure.

Post a 2010 investigation into foreign U.S. listed operations, the SEC found substantial evidence of abuse of dormant shells, and in 2012, in the aftermath of the Chinese reverse merger bust, took a stand, suspending trading on nearly 400 said shells to prevent fraudulent investors from “hijacking” the corporate entity, and pumping and dumping the stock [4]. Per Robert Khuzami, the SEC Director of the Division of Enforcement in 2012: "Empty shell companies are to stock manipulators and pump-and-dump schemers what guns are to bank robbers – the tools by which they ply their illegal trade" [4].

By contrast, the private company in a SPAC transaction takes ownership of a clean shell with no previous history nor operations. There are no potential liabilities associated with past operational activities as there are with dormant shell mergers. The SPAC Sponsors also retain ownership, unlike reverse mergers where the surviving management and Board of Directors is that of the acquired operations company. This, coupled with the opportunity for SPAC investors to redeem their investment if they do not approve of the merger, makes it more challenging for stock manipulators to use SPACs for pump and dump schemes.

If SPAC investors do not approve of the merger, they have the option to redeem their investment, which tends to put a floor under the stock price up to the date of merger completion. The option to redeem did not exist for RTOs.

Furthermore, SPAC shareholders have the right to vote on the proposed merger, and if the vote fails to win approval, the Sponsor will likely have to liquidate the SPAC and return funds to investors.

As more SPACs successfully complete business combinations (the De-SPAC process), the pool of target companies in both size and variety has ballooned. RTO mergers and, in earlier years, SPAC targeted companies were perceived as poor quality and not yet ready to pursue the rigor of a traditional IPO roadshow and the reporting requirements of a public company.

However, the last couple of years have seen mainstream acceptance of SPACs and greater involvement of experienced financiers and businesspeople in SPAC sponsorship. Completed mergers and merger candidates now involve a wide variety of companies and industries including late-stage Venture Capital and Private Equity investments, and several “Unicorns” (private companies with greater than $1bn valuations).

The perception is growing that the SPAC merger process is faster, cheaper, and has greater certainty of merger proceeds than traditional IPOs. All this has meant that many firms that could attract interest via a traditional IPO, are choosing to pursue a SPAC merger instead. This has been particularly true for Silicon Valley firms dissatisfied with the traditional IPO process.

| Sector | Count | Percentage | $ Raised | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aerospace | 6 | 1.40% | 1,375,836,192 | 1.05% |

| Cannabis | 8 | 1.86% | 1,338,255,039 | 1.02% |

| Consumer Products | 28 | 6.51% | 8,064,292,349 | 6.18% |

| Education | 4 | 0.93% | 927,359,284 | 0.71% |

| ESG | 35 | 8.14% | 10,197,037,167 | 7.81% |

| Financial Services | 7 | 1.63% | 2,308,904,288 | 1.77% |

| Fin-Tech | 22 | 5.12% | 9,070,200,129 | 6.95% |

| Fin-Tech & Financial Services | 3 | 0.70% | 105,570,000 | 0.08% |

| Healthcare | 38 | 8.84% | 8,808,864,682 | 6.75% |

| Industrial | 14 | 3.26% | 4,967,873,006 | 3.80% |

| Insurance | 3 | 0.70% | 727,250,000 | 0.56% |

| Life Sciences | 19 | 4.42% | 2,518,485,074 | 1.93% |

| Multiple | 42 | 9.77% | 11,827,648,696 | 9.06% |

| N/A | 67 | 15.58% | 28,894,868,884 | 22.13% |

| Real-Estate | 7 | 1.63% | 1,372,483,577 | 1.05% |

| Sports, Media and Entertainment | 25 | 5.81% | 6,903,257,402 | 5.29% |

| Technology | 92 | 21.40% | 28,758,820,667 | 22.02% |

| Travel & Dining | 10 | 2.33% | 2,407,170,445 | 1.84% |

| TOTAL | 430 | 100.00% | 130,574,176,881 | 100.00% |

Source: https://spacinsider.com/stats/

That said, the SEC cautioned in a December 2020 Investor Bulletin, to consider whether attractive business combinations will become scarcer, as an influx of SPACs search out targets [5]. SPACs, which are granted only a two-year window to complete a merger (unless investors agree to extend the search), may find themselves “settling” with a target to avoid liquidation. Additionally, with the general requirement that the target is valued at least at 80% of the SPAC Trust, concerns arise around Sponsors’ willingness to overpay for an asset, especially if anxious to close a deal. Risks of misaligned sponsor and investor interests, compounded by increased public demand for SPACs, are a catalyst for the SEC’s recent guidance on conflict of interest disclosure associated with SPACs [6].

With their growth in popularity, and the high returns generated for Sponsors, SPACs are attracting a wide range of players. In some cases (“Celebrity SPACs”) well-known media and sports figures are seen as “cashing in on their fame.” However, other SPACs are attracting experienced financiers and ex Fortune 500 executives, comfortable, for example, with handling the stringent SEC requirements associated with public companies. Among these are Goldman Sachs, Pershing Square, and Apollo Global Management. Such deals (“HQ” deals in these charts) have been far more successful than “NotHQ” deals which lacked experienced Sponsors.

Former Chairman of the U.S Securities and Exchange Commission, Jay Clayton noted that the SPAC concept "actually creates competition around the way we distribute shares to the public market," and "competition to the IPO process is probably a good thing."

He went on to say, however, that "for good competition and good decision making, you need good information…At the time of the transaction, when [shareholders] vote," the SEC wants to make sure "they're getting the same rigorous disclosure that you get in connection with bringing an IPO to market." [7]

The new SEC Chairman, Gary Gensler, said in testimony to the Senate that his enforcement agenda will include heightened scrutiny of SPACs [8].

The SPAC boom continues apace, taking a larger and larger share of the IPO market over 2020 and 2021. While there are strong signs of “irrational exuberance”, “hype” and “frenzy” in this phenomenon, as there were in the prior RTO boom in 2010-2012, there are equally strong reasons to believe that SPAC issuance will be a permanent feature of the IPO market going forward: most notably the involvement of experienced Sponsors, the higher quality of merger deals and merger candidates, and the perception by issuers that SPACs are faster, cheaper and have greater certainty of merger proceeds than traditional IPOs.

[1] “Investor Bulletin: Reverse Mergers”, SEC Office of Investor Education and Advocacy, Securities and Exchange Commission, June 2011

[2] “How they fell: The collapse of Chinese cross-border listings”, McKinsey & Company, David Cogman and Gordon Orr, December 1, 2013

[3] “The SPAC Bubble Is About to Burst”, Harvard Business Review, Ivana Naumovska, February 18, 2021

[4] “SEC Microcap Fraud-Fighting Initiative Expels 379 Dormant Shell Companies to Protect Investors From Potential Scams”, https://www.sec.gov/news/press-release/2012-2012-91htm, Securities and Exchange Commission, May 14, 2012

[5] “What You Need to Know About SPACs – Investor Bulletin", US Securities Exchange Commission, December 10, 2020

[6] “Special Purpose Acquisition Companies; Division of Corporation Finance; Securities and Exchange Commission; CF Disclosure Guidance: Topic No. 11”, Securities and Exchange Commission, December 22, 2020

[7] “SEC Chairman Jay Clayton on Disclosure Concerns Surround Going Public Through a SPAC”, CNBC Television, September 24, 2020

[8] “New SEC Chair Gary Gensler Could Push for SPAC Regulation”, MSN Money, January 20, 2021

* Source