Canadian Hydrogen Observatory: Insights to fuel…

Article

Most businesses experience business disruption in some shape or form, be it a change in the market environment, a step change in technology, unforeseen micro, macro or political events or other changes impacting the top line. Depending on the circumstances different strategies are deployed to address the risks, but one thing is universally certain for all businesses if they are going to ride the storm: they will need to manage cost.

Reducing costs (Opex and Capex) will help your business manage a period of disruption or crisis by:

1. Staying viable during the downturn.

2. Protecting existing assets and key workforce so you are ready to take advantage of opportunities during or after the downturn.

This period of uncertainty also means that many investments in the pipeline will be scraped or halted in the short-mid term. But once the downturn is over, the business needs to be ready to make new investments to grow and/or exploit new opportunities. Managing cost effectively now, will better position businesses to have the funds available in the future to start investing again.

There are plenty of cost reduction, cost optimisation and efficiency improvement methodologies and initiatives that individually and collectively contribute towards reducing cost. In this article we outline the cost reduction methods that provide the most benefit and deep dive specifically in the hardest but most effective approach: Organisation Design.

First things first, the business must manage cash. In this context, businesses have to get a clear view of their cash position and then evaluate the impact of the disruption and how that affects cashflows. Leaders should forecast cash flows based on scenarios and stress test these forecasts. At the same time financing options should be considered and utilised, including government instruments.

Cash management is not a cost reduction process but is the very first step a business needs to take in a crisis, prior to kicking-off any cost reduction or other initiatives. After a business gets a good handle on its cash position and takes all the necessary steps to ensure its viability and survival, then it needs to examine how to manage cost.

There are plenty of cost reduction, cost optimisation and efficiency improvement methodologies and initiatives that individually and collectively contribute towards reducing cost. The purpose here is to identify which initiatives are more relevant and effective in the current crisis context and would provide the most benefit in the short and medium term.

Overhead costs are often neglected as they are not associated with the production of outputs (they are not part of the core value chain) and frequently are allocated in multiple budgets as cost line items. As a result, budget owners often treat them as ‘the cost of doing business’ and do not scrutinize them or measure their effectiveness as rigorously as they do with operational or production costs. An overhead costs analysis can deliver quick wins in cost reduction and efficiency improvement without affecting the core of the business.

Discretionary spend on non-essential activities is easy to cut in times of financial turbulence. But even if performance is healthy, discretionary spend can be re-allocated to be spent on activities that better serve the mission, vision and culture that the business wants to promote.

Effective management of 3rd party suppliers via the Procurement function is an area that can bring substantial benefits. Actions could include stopping or severely restricting discretionary spend, centralising procurement functions, implementing global framework agreements, renegotiating contracts (unit price and payment terms) or finding new suppliers.

Management of suppliers is a common go-to strategy to reduce costs. In times of large-scale disruption, this becomes even more prevalent because the suppliers will themselves be enduring the same challenges and will be willing to make more concessions (in price and/or accepting longer payment terms) to retain revenue. Of course, this does not mean that a business should be changing every supplier overnight. Key strategic suppliers should be handled carefully, weighing the pros and cons of each action before any major decisions are made.

The business may also need to procure new products or services to respond to the crisis (e.g. in support of remote working, strengthening online/digital capabilities etc.). Doing it right first time reduces risk and helps avoid future costs.

Budgets for most companies are typically set at the end of the previous financial year and are reviewed periodically throughout the current year (commonly called incremental, static or traditional budgeting method). When budgets are set, a number of assumptions are made, many of which will not be valid anymore because the massive disruption to the market was not part of scenario planning.

As a result, a business needs to address a dual challenge: How to manage the budget now (short-term) and what to do moving forward into the next financial year.

Given the current levels of uncertainty, the business should in the short-term move to a cycle of budgeting and re-forecasting at short, regular intervals to provide visibility of spending at all times and allow for reactionary measures to be taken based on how the crisis evolves.

Moving to the next financial year and given that the previous year’s budgets would no longer serve as a good baseline, it is a great opportunity to rethink the way the business builds and monitors budgets. Traditional budgeting methods most often involve migrating costs from one year to the next without truly challenging them. Changing the way a business runs budgets, reaps great results in reducing costs the first year. But it is a long, painstaking process that many businesses simply avoid altogether.

There is no one single method that is universally accepted as the best one. The preferred method depends on the type of business, industry, culture and size as well as the approach to budgeting by management and the willingness to invest time and resources in the process.

For example, a simple and more tactical approach is to reduce budget by a fixed percentage and delegate to managers to implement or set a number of targets and initiatives and budget around them. A more agile method to budgeting for uncertain times is Dynamic Budgeting while the method of building a budget from scratch based on what is needed (as opposed to what was used last year) is Zero Based Budgeting.

A business that has gone through a period of disruption has to address its workforce and how it organises itself to be fit for purpose for the new environment. This process can achieve substantial cost reductions.

There are a great number of ways and methods to achieve this. There is no one single solution that fits all. Some examples are: Value chain analysis and activity-based costing, workforce segmentation, shared services, outsourcing, delayering, redundancy, redeployment and restructuring. In the next sections of this article we deep dive into this topic and analyse the best approached in using organisation design to reduce cost.

Cost reduction initiatives without any organisational change element are ultimately limited to the benefit they can provide. Stand alone cost reduction projects (e.g. on Procurement, overheads etc) aim at improving performance in a specific and targeted part of the cost base. These can be very effective as a percentage of the addressable spend targeted, but can only go as far as the scope allows.

In order to address a larger cost base, the business needs to make changes to its organisation design and the workforce. In taking early action, the business may be able to avoid harsher measures in the future (e.g. large-scale divestment or closures) that might have a greater impact to the business and its workforce.

There are a variety of approaches to delivering cost reduction through organisation design:

1. Target and Delegate

2. Integrated Design

3. Activity analysis

In some circumstances, the preferred approach will be obvious, but for most cases it is not. There is no one-size-fits-all solution. Moreover there are situations where businesses implement more than one approach at the same time; i.e. from the CEOs perspective it could be a Target and Delegate approach, but then the individual BUs can use Integrated Design or Activity Analysis to get the desired results.

The first activity that needs to happen is a scoping exercise. This is where the business defines what the problem is, what is in scope and what is not and what it is that it wants to achieve.

Alongside scoping, the business needs to consider a number of important questions, the answers of which will affect the decision on the desired approach. Examples are:

· What are the major talent areas you want to retain no matter what?

· What are the core and non-core business activities?

· What other ongoing initiatives will impact your workforce decisions? (e.g. outsourcing, automation etc.)

The first and simplest approach is ‘Target and Delegate’. This is when leadership decides on a target based on the needs of the business and then delegates the implementation to managers of regions, functions and/or business units without much support or guidance.

The target given to management can come in the form i) an absolute number, e.g. reduce resource costs by £2m or reduce headcount by 100, or ii) a percentage e.g. reduce resource cost or FTE number by 15%.

· It is simple and straightforward.

· It is easily understood and communicated.

· The results can be tracked.

· It can be difficult to define and agree how targets are set and allocated between BUs.

· This approach does not provide clarity on how the cost reduction will be carried out, leading to BUs taking different approaches and communicating inconsistent messages.

· It often ends being an unfair and reactionary process driven by instincts and personalities rather than process and data.

· The managers tasked with implementation may not have the experience and expertise required.

· There may be dependencies between different areas of the business which will not be addressed if the cost reduction is carried out in siloes.

The integrated design approach is one where the business will set up a dedicated team in a programme of work that will address the entire corporation (across BUs, regions, functions) in a well thought through, step by step process.

The programme typically starts with an As-Is analysis and diagnostic that details the current status of the organisation and identifies what works well, what does not and the opportunity areas for improvement. Then the programme is divided into workstreams which deep-dive into specific areas of the business (e.g. BUs, regions, functions etc.), coordinated by a central team.

This is a very common and effective approach deployed by businesses when they want to address large parts or the whole of the organisation concurrently. In the context of cost reduction, it is highly recommended as the process might involve layoffs; therefore, decision making must be supported by well thought through data-driven insights.

The initial scoping exercise and as-is analysis will determine how deep and complex the programme approach will be. An easy way to think about this is to break it down in three types:

A. Simple approach

With this approach the business does not look to do major restructuring and Target Operating Model changes, but rather retain the core structure and optimize its segments. Example methods of doing that is optimising spans and layers of control, benchmarking and aligning functions with industry averages, simplifying reporting hierarchies etc. While quick and tangible, it can be hard to realise substantial and sustainable savings from this approach and it can be very disruptive.

B. Initiative based approach

This approach is based on performing major changes to the existing structure and breaking them up as separate initiatives (often but not always mirroring programme workstreams). These initiatives should be divided based on the scope they cover. For example, a programme with three initiatives could comprise of: merging the Sales and Marketing teams, centralising regional procurement teams in one central function and creating a shared service centre for Accounts Payable and Accounts Receivable functions.

C. Zero Based approach

This is the most radical approach and involves starting a brand-new design on a blank sheet of paper, irrespective of how the organisation is structured today. This is obviously the most challenging and difficult to implement method but can potentially deliver the most benefits. In the context of Covid-19 where businesses might be looking for solutions with more immediate returns, this approach might not be appropriate due to its long lead and implementation times.

An integrated design approach is likely to trigger more detailed work on the back of its recommendations such as a deep dive into activity analysis (see Approach 3) or HR policy changes (e.g. compensation and benefits, recruitment, performance management).

· It is more strategic compared to ‘Target and Delegate’ and looks into the organisation as a whole as opposed to its segments individually.

· It allows for integrated designs and trade-offs between BUs, Regions and Functions.

· It utilises specialist full time expertise in a programmatic approach.

· Delivers objective and data driven designs backed by well thought through decisions.

· It takes longer than Target and Delegate.

· The high impact of change may trigger resistance internally, which requires rigorous change management and communication in order to be successful.

· The central team managing the programme of work will not understand the entire business end-to-end which may result in very ambitious or unrealistic proposals put forward.

Activity analysis is the most detailed approach and involves deep diving in all people-driven activities, process, inputs and outputs of how the business operates. This will provide an understanding how much effort is currently being put into each activity and allow to re-evaluate whether it is worth changing or improving via reorganising the business.

In simple terms, it analyses in depth ‘what people do’ and ‘how they do it’. Understandably this can be a very time-consuming analytical exercise and it is difficult to implement across the whole organisation, especially if it is large. Most often, certain parts of the organisation with high improvement potential will be selected from a Integrated Design type programme for a deep dive rather than kick-off with a full end-to-end activity analysis from the very beginning.

· It is as analytical and objective as it possibly can be.

· It provides the business with insights that were not previously known and can trigger further non organisation design related improvement initiatives. It is common after the organisation realises the improvement potential from an activity analysis to kick-off agile, six sigma or other operational improvement programmes.

· Different approaches can be taken for different types of business activity

· The process can be at times demotivating and disruptive to employees.

· The information collected is not always accurate or objective.

· Qualitative measures are more difficult to evaluate and analyse that quantitative ones, while people (intentionally or not) might be providing false or misleading information which then is used as the basis for the analysis.

· It is not suitable for all types of activities. For example, the activities delivering a successful marketing campaign are not always the same and cannot be modelled in a one size fits all approach.

It is important to note that there are a number of cost-driven workforce actions that can be taken that do not require organisation design. Such temporary actions are taken by businesses all the time and used as easy levers that management pulls to manage cost in the short term. Examples are:

· Freeze on hiring, promotions or transfers.

· Reduction, postponement or cancellation of training schemes, graduate schemes or internships.

· One-off reduction in annual bonuses

· Voluntary redundancy and accelerated retirement schemes.

In this section, we review how to apply workforce segmentation to accelerate and gain additional value from Organisation Design. The end goal is to build a programme that focuses on initiatives that can deliver business objectives without unnecessary disruption.

Cost reduction is a highly disruptive activity, with significant human and economic consequences. Some organisations start with the principle that the burden of cost reduction should be applied equally across each area of the business. This approach to managing cost is highly disruptive and could cause more harm than good.

Workforce segmentation is the discipline of grouping the workforce into distinct segments with common characteristics such as business unit, function, performance, cost, skills, contribution to business value etc.

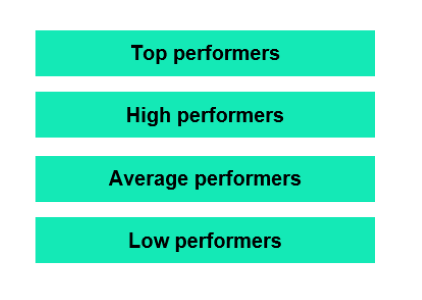

In Workforce Planning, critical segments are those which are critical to business outcomes and which hold capabilities that are difficult to acquire or replace. Extra effort and planning goes into ensuring that these roles are, and will always be, staffed. A typical method of outlining this is shown below:

The same reasoning should be applied when looking at workforce segments from a cost perspective. In the context of cost reduction, critical workforce segments are those that have the largest room for improvement and can generate the most benefit.

After identifying multiple segments as candidates for being critical, you will have to evaluate and select which ones to reduce cost based on:

If you apply this approach, you will build a programme that focuses on initiatives that reduce costs, have small impact on business value, and are relatively easy to implement.

Prior to kicking off implementation, it is important to understand the impact workforce changes have on business outputs and to validate those decisions with current business performance and business strategy.

Segments that belong or contribute to the core value chain are those directly related to the delivery of a product or service (e.g. manufacturing, sales). Support functions provide support to the core (e.g. Finance, IT, HR). Very different analyses and questions are needed for each.

For example, segments related to the core value chain have a direct impact to product output. Any change there might affect production quantity or quality. Reduction may be justified in these areas under specific contexts, such as if demand is down or the business is pivoting away from a product line. Otherwise it may be best to simply optimise or avoid altogether.

Support functions on the other hand are less related to production and can be changed via different strategies such as creating shared service centres, automation, or outsourcing.

Future value oriented segments are those that focus on the design and planning of strategies and activities that create and deliver value in the future. Such workforce segments are typically found in strategy, marketing, and R&D departments. Reducing cost in these segments may not have a direct impact today but can restrict growth in the future.

Workforce segmentation covers a wide range of segmentation methods that span from categorising people based on organisation structure, skills and capabilities, business performance, or other methods.

In this section, we examine some typical examples of workforce segmentation.

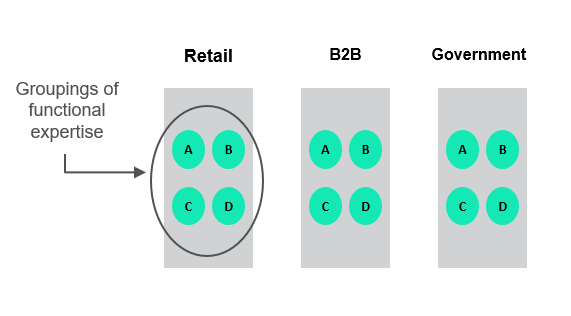

The workforce is segmented based on distinct business units that operate as separate businesses/services under one group.

The workforce is segmented based on geography; with each region incorporating all products and functions and owning its own P&L.

The workforce is segmented around specialist activities and competencies which may be in functions or spread across multiple business units or geographies.

The workforce is segmented based on business lines/portfolios of products with common characteristics.

The workforce is segmented based on business assets. This is common in businesses that operate a small number of very large, capital intensive assets.

The workforce is segmented based on customer groups.

The workforce is segmented based on the workflow stages of making a product or delivering a service. Teams are based around key process steps and may contain a mix of functional skills.

The workforce is segmented based on performance. This type of segmentation is not related to structure, but certain teams might collectively have greater aggregations of high or low performers.

Driven by highly quantifiable and measurable outputs; e.g. sales organisations.

Creating single segments and analysing them is very important but, unfortunately, it is not enough. This is because they only investigate one dimension of the workforce. For example, assume that we identify that the ‘Soda’ business line in the Product-based segmentation illustrated above has significant room for improvement. Is that information enough? No. Because within that segment you will find all different types of departments (production, sales) and functions (HR, Finance, IT). The cost reduction opportunity might reside only in part, and not the whole, of this segment. Therefore, you will have to apply a second dimension in the segmentation, e.g. ‘Soda’ business line by department and function.

After this, you may realise that two functions (e.g. Finance and IT) within the ‘Soda’ segment are the most critical segments for cost reduction. Again, that might not be enough. In this case, you should add a third dimension, e.g. performance, skills, value-added etc. to finalise the segmentation.

To help you understand segments better, you can use data-driven, deep-dive analysis techniques. No matter the characteristics of a segment, there are numerous data-driven insights that can be obtained and analysed to support decision making. Some examples are shown in the charts below.

No matter how challenging this period might be, it is paramount that the business never neglects the importance of its people and the vital role they play. It is people that will make the decisions, implement them, and reap the rewards or face the consequences. In difficult times, it is important to treat people with respect, be transparent, and bring them along the journey.

We bring decades of transformation experience and innovative data science-based solutions to help you rapidly assess the current-state, examine future-state options, and implement impactful change for your organisation. We deploy sophisticated analytics and digital tools alongside our human subject matter experts, ensuring you receive support tailored to your organisation’s context and needs. Our consultants rapidly assess your workforce, financial, and competitor data and define actionable insights that guide every step of the project, from assessment, to detailed design and implementation. Our Transformation Hub, an online portal of proprietary tools and aids, means that you have end-to-end visibility on the design process, with downloadable tools at your fingertips, on-demand, around the clock.

In the near-term, our team can help you understand how your customer demand is changing and how to redeploy your workforce from areas of relatively low-demand to areas of high-demand or higher priority. We can also help you to align near-term workforce decisions to operational measures and targets to ensure you have an agile, nimble base from which to grow in the post-COVID world.

In the medium-term, our team can help you model options for the size, shape, and design of your future organisation. We obtain, aggregate and cleanse the most relevant data and then quickly assess your as-is state, delivering quantitative and qualitative insights that help you cut costs, define opportunities, and build a more resilient organisation. We start by helping you create design principles centred on your post-COVID business strategy and objectives. From there, we help assess future-state designs that maximise key variables like profitability, long-term growth, or increased organisational resilience. Lastly, we will help manage the full implementation via our dedicated transformation PMO offering.