Carbon Accounting Management Platform Benchmark…

The rapidly changing regulatory environment and investors' expectations regarding sustainability highlight the importance of data and Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) ratings. Here we will provide updates on changes to the ESG data market, and challenges for financial services.

The ESG data market is changing, and the landscape of ESG data providers - many of which also rate ESG performance - is evolving rapidly.

ESG performance rating consists of evaluating companies by giving three grades for Environment, Social and Governance aspects. Each grade is based on quantitative and qualitative information, and a weighted average of these three grades is then calculated to attribute a global score to the company.

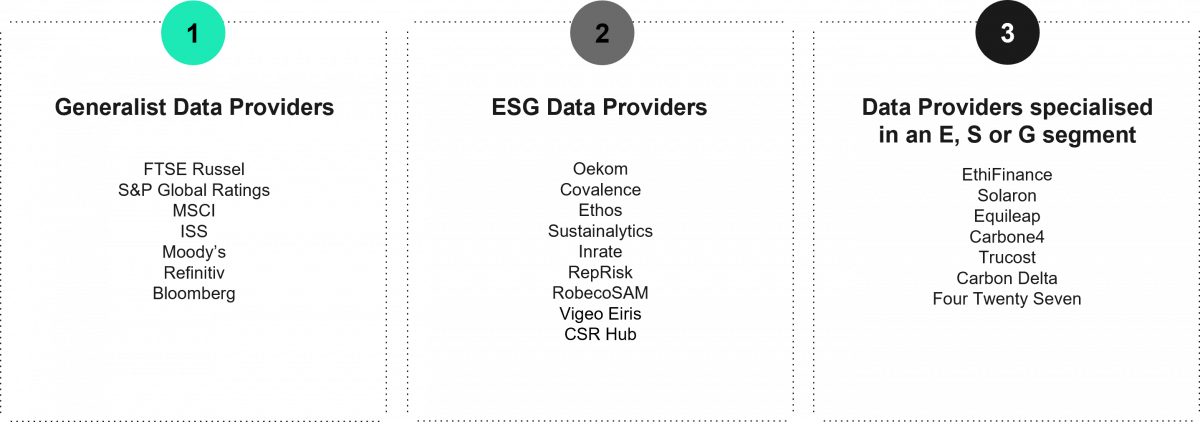

We can categorize ESG data providers into (Figure 1):

The landscape of ESG data providers

The landscape of ESG data providers is undergoing a transformation. There were frequent mergers and acquisitions that contributed to the formation of a US/UK-based oligopoly (Figure 2) of generalist data providers. As FMA pointed out in a recent document, between 2015 and 2020, 21 buyouts took place, 14 of which targeted a European company. Most of these transactions were carried out by US/UK-based players, and today 80% of data providers are linked to US/UK-based companies.

London Stock Exchange → Beyond Ratings, Refinitiv

MSCI → Carbon Delta

Morningstar → Sustainalytics

Moody's → Vigeo Eiris, Four Twenty Seven, SynTao Green Finance

These buyouts are explained by the rapid growth of the ESG data market: according to Opimas, spending on ESG data tripled between 2016 and 2019 to reach $900 million.

Paradoxically, there are almost exclusively US/UK-based data providers who may capitalize on European ESG regulations. If the data providers are not European, the EU may not be in a good enough position to expand its vision & model for more sustainable capitalism. Denounced by the Financial Market Authority (FMA) and its Dutch counterpart in December 2020, no regulations control the sourcing and calculation methodology of these data providers, even though progress is possible.

As part of the European Green Deal, regulators are seeking to incentivize investments in “sustainable” assets putting the spotlight on ESG data providers. This is a double-edged sword: while regulations contribute to data provider growth, they also highlight methodological shortcomings.

Faced with new European regulations and ever-increasing reputational risks, financial services firms are now expecting more effort from data providers, most of whom cannot cite their sources, to explain their data processing methodologies or describe their rating processes.

In addition, it should be noted that data sourcing is very costly, with firms sometimes paying up to 10 different ESG data providers for a cross-sectional view of the market.

In its report on the outlook for sustainable finance, the OECD highlights the methodological shortcomings of ESG rating providers. For a given group of companies rated on both extra financial and financial aspects by data providers, the correlation coefficient is only 0.4 for extra-financial ratings compared to more than 0.9 for the financial evaluation of companies.

The contradiction between the importance of ESG data for investors, and the inability of data providers to clearly explain their sourcing and rating methodology, creates a dilemma for financial services actors who seem to opt for a third method: external sourcing and internal data processing. The new business model of Sustainalytics, which has been selling raw data since August 2020, demonstrates this new trend.

Faced with this observation, the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) reacted on January 29, 2021, by urging the European Commission to regulate ESG data providers to ensure the quality and reliability of the data.

It is well-known that the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR), which comes into force on March 10, 2021, will require financial services players to publish precise indicators concerning the extra-financial performance of companies. This forces one to consider whether these regulations for ESG data providers are coming too late.

The hope for European authorities is that greater transparency in the calculation of ratings will result in a more competitive environment where each of the players will try to improve their rating process, thus allowing for a convergence of ratings. The challenge is to give investors confidence in this new way of reading company performance, the success of the European Green Deal partially depends on this.

Nevertheless, methodological transparency is not a panacea: ESG data must be made available to as many people as possible so that ratings become more accurate and therefore relevant. It is also true on the qualitative side of companies’ screening, as the lack of information regarding controversies represents a major barrier to action for investors.

The revision of the Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD), which will take place in the first quarter of 2021, should be the first step towards this goal, and European authorities are even considering the creation of a European ESG database as part of the Capital Markets Union (CMU) action plan.